Arabic Bible: No Reason Why Language Should be an Obstacle

There are descendants from ancient Arab Christian clans that didn’t convert to Islam, hence they follow Christianity as a result of the alliance their predecessors have formed with Christian Byzantium. There are over 1 million people of Arabic descent that consider themselves Christian even to this day, and since the bible is the most widespread book there is, it too was adapted to their native tongue.

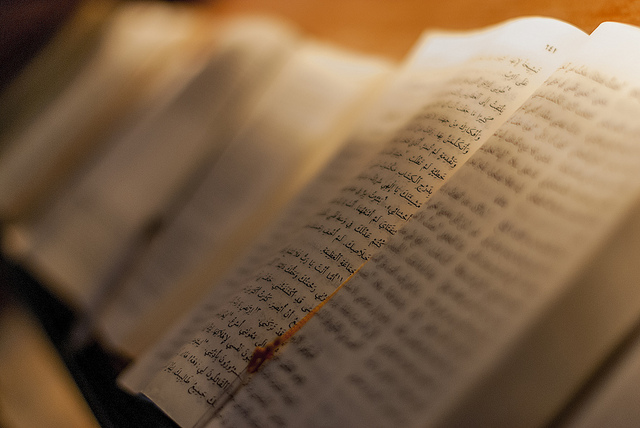

The Arabic Bible, as it’s called nowadays, was first translated around the 8th century from the Hebrew Bible, the earliest fragment being a text of Psalm 77. The oldest discovered Arabic Bible dates back from the 19th at the Saint Catherine’s Monastery. Its manuscript was created in 867 AD and it includes marginal comments, biblical text, glosses and lectionary glosses.

In 1671 the whole Bible was published in Rome by the Catholic Church. The translation was done by Sergius Risi – Archbishop of Damascus, Vicenzo Candido – professor of theology at the College of Saint Thomas in Rome, and Francis Britius. One of the earliest translations to Arabic was initiated by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Thanks to their initiative, the orientalist Samuel Lee, alongside his pupil professor Thomas Jarett created one of the best Arabic translations of the Bible.

The most popular translation was funded by the Syrian Mission and American Bible Society – the Van Dyck Version. It started around 1847 in Beirut, and it was led by Eli Smith. After his death, it was completed by Cornelius Van Allen Van Dyck in 1860, followed by the Old Testament in 1865. The original manuscript is still preserved in the Near East School of Theology in Beirut, and since its creation, around 10 million copies have been distributed. It has been accepted by Protestant and Coptic churches and is mostly based on the same Textus Receptus as the King James English version – following a literal style of translation.

The Van Dyck translation was done in the revival period of the modern standard Arabic as a literary language, and for this reason many of the terms coined didn’t enter into common use. In addition to archaic and obsolete terms, this translation uses religious terminology that non-Christians and Muslim readers probably won’t understand. It’s also worth noting that Arab Muslims reading it will quote its style differently than the one used in the Qur’an. What’s also worth noting is that the religious terminology familiar to Muslims isn’t used very much in this version of the Bible, as is the case in the majority of Arabic versions of the Bible.